Complications should be less using a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy. Laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH), defined as the laparoscopic dissection, ligation, and division of the uterine blood supply, is an alternative to abdominal hysterectomy with more attention to ureteral identification.1-3 First done in January, 1988,4 laparoscopic hysterectomy stimulated a general interest in the laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy as gynecologists not trained in vaginal or laparoscopic techniques struggled to maintain their share of the large lucrative hysterectomy market. A watered down version of LH called LAVH (laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy) was taught by industry and became known as an expensive over-utilized procedure with indications for which skilled vaginal surgeons rarely found the laparoscope necessary.

LH remains a reasonable substitute for abdominal hysterectomy. Laparoscopically assisted hysterectomy is a cost-effective procedure when done with reusable instruments; it is a safe procedure, even when performed by a variety of gynecologists with different skill levels, and its adoption can decrease abdominal incision hysterectomies.5

A laparoscopic hysterectomy is not indicated when vaginal hysterectomy is possible, i.e., when the uterine vessels are readily accessible vaginally. Most hysterectomies currently requiring an abdominal approach instead of vaginal surgery may be done with laparoscopic dissection of part, or all, of the abdominal portion followed by vaginal removal of the specimen. There are many surgical advantages to laparoscopy, particularly magnification of anatomy and pathology, access to the uterine vessels, vagina and rectum, and the ability to achieve complete hemostasis and clot evacuation. Patient advantages are multiple and are related to avoidance of a painful abdominal incision. They include reduced duration of hospitalization and recuperation and an extremely low rate of infection and ileus.

The goal of vaginal hysterectomy, LAVH, or LH, is to safely avoid an abdominal wall incision. The surgeon must remember that if he/she is more comfortable with vaginal hysterectomy after ligating the ovarian or utero-ovarian vessels, this should be done if possible. Laparoscopic inspection at the end of the procedure will still permit the surgeon to control any bleeding and evacuate clots, and laparoscopic cuff suspension can be done to limit future cuff prolapse.

Patient safety is the surgeon’s primary responsibility. Thus “learning curve” injury must be minimized. Unnecessary surgical procedures should not be done because of the surgeon’s preoccupation with the development of new surgical skills. Complications are an inevitable by-product of any surgical procedure, but everything possible must be done to reduce this risk. Obviously, the surgeon requires a strong background in operative laparoscopy and sufficient training to demonstrate proficiency.

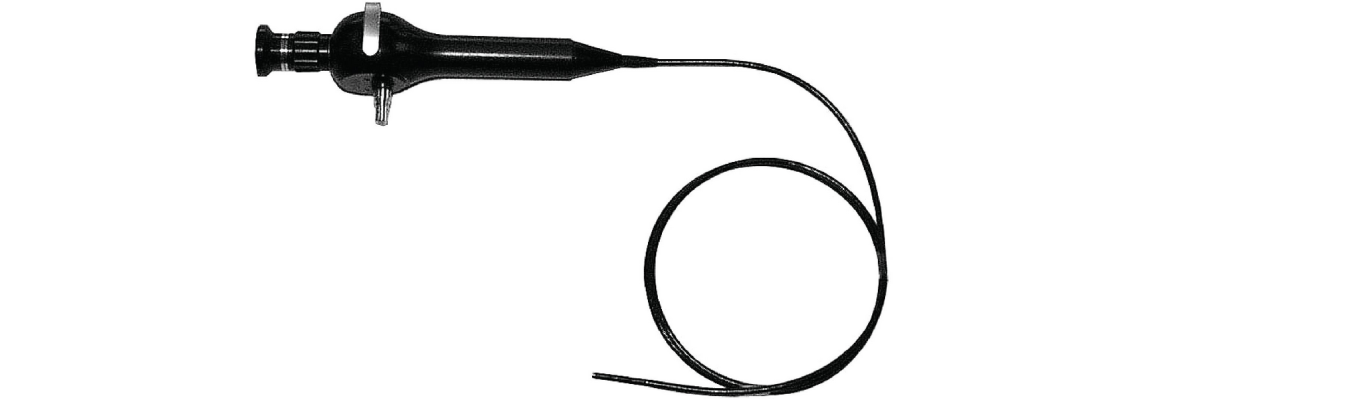

The operative environment must be prepared for laparoscopic hysterectomy. Equipment must be available, functional, and a backup plan in place to cover any unanticipated malfunction. Additionally, and of equal importance, is the competence level of the operative team. Anesthesia, nursing, and the surgeon must share the same operative goals and actively cooperate to achieve them. Frequently neglected is the need for education of the postoperative support staff.

Reduction of risk begins with a detailed patient history and comprehensive physical examination, frequently including ultrasonographic confirmation of physical findings. Medical clearance is sought on anyone with any historical or physical suggestion that could lead to possible operative compromise. Since, in most cases hysterectomy is an elective procedure, the patient is counseled extensively regarding the range of currently available options appropriate to her individual clinical situation. In 1997 it is clearly not acceptable to advocate hysterectomy without detailing the risks/benefits of other intermediary procedures.

Since 1987, in my first 5 years experience with LH, no patient was denied a vaginal or laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy except when advanced cancer was suspected. As my practice is largely referral, this represents a significant degree of pathology. Only 9 of my first 123 women had benign pathology; in these cases hysterectomy was done for pelvic adhesions, and/or persistent hypermenorrhea. Laparotomy was not needed regardless of size or location of uterine fibroids or extent of endometriosis. Only one woman with extensive bowel adhesions and endometrial cancer underwent laparotomy to complete the hysterectomy and to reinforce four small bowel enterotomy repairs. This supported my belief that most hysterectomies presently performed with the abdominal approach could be done laparoscopically.

While conversion to laparotomy when the surgeon becomes uncomfortable with the laparoscopic approach should never be considered a complication, conversion rates should be monitored to safeguard the consumer’s right to have this procedure performed by a competent laparoscopic surgeon. Surgeons who do over 25% of their hysterectomies with an abdominal incision should not stretch their ability and degree of expertise with a laparoscopic approach to their patients.